Our new article, published in Children’s Health Care, explores how parents have experienced children’s health care for hypermobility Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (hEDS) and hypermobility spectrum disorders (HSD). This blog covers our research journey, the key findings, and my reflections on conducting the research.

The research journey

This research was part of my Master’s degree in Health Psychology at Coventry University and was supervised by Dr Gemma Pearce. The project began after Gemma had spoken to Kay Julier from Ehlers-Danlos Support UK, who identified a research need for children living with hEDS/HSD. I had also previously completed a student placement year in a hospital-based youth service, which sparked my interest in children’s health care. Though I initially had limited knowledge of hEDS/HSD, I had heard of EDS through friends who had been diagnosed, and eventually became more familiar with the conditions. The research plan was developed by Gemma and myself, we gained feedback from Kay, and Dr Emma Reinhold tested the online survey for us.

The study

Once we received ethical approval, EDS UK and HMSA helped us to share the online survey with members and we posted about it publicly over social media. As well as parents of children with diagnosed hEDS/HSD, we felt it was important to hear from parents whose children may have hEDS/HSD but had not been diagnosed, particularly because research (and hEDS/HSD charities) had reported that adults can experience long journeys to diagnosis. We also included previous names related to hEDS/HSD, such as EDS type III, EDS hypermobility type and Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (JHS), to ensure that the research included a range of relevant health care experiences for these conditions. For this study, we heard from parents in the UK to understand what is happening within the UK’s healthcare system. To collect more recent experiences, we also recruited parents whose children were currently 16 years or younger.

The first part of the study invited parents to complete a survey about children’s health care for hEDS/HSD. In total, 297 parents reported about their experiences with diagnosis, different health professionals, and rated different aspects of health care for their child(ren).

We then interviewed 13 of these parents to learn more about different positive, negative, neutral and mixed experience. This was so that we could understand what good health care looks like, and where improvements might be needed.

The findings

Overall, the findings from parents in this study advocated for children’s health care for hEDS/HSD to be better centred around children and families. Some of the key findings are below:

A lack of awareness and knowledge about hEDS/HSD among health professionals was often reported by parents. Inadequate professional understanding was a key factor in negative health care experiences for around three quarters of parents. Interviewed parents also described that they often had to become experts themselves to be able to advocate for their children.

‘‘Professionals have either not heard of it or don’t really know a lot about it and that’s what the big problem is.’’

Experiences with health professionals were mixed. On average, parents scored different types of health professionals around 5/10, although private professionals scored a positive 9/10. Parents explained that private health care was sometimes necessary because of delays and challenges in the NHS. Parents also described that ‘good’ health care included listening to families. However, some families had instead experienced stigma, disbelief, accusations, and misdiagnoses such as psychological conditions. These led to some children and parents wanting to avoid health professionals.

‘‘My GP for a while just said, ‘growing pains, growing pains, it’s fine’, so I really had to push for that.’’

The way the health care system works was also important to families. Parents reported that accessing specialists and treatments was often not straightforward, because specialities were not effectively joined up or beneficial treatments were not easily available. Often, parents had to play a key role in organising their children’s health care.

“There’s no joined-up care for Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and if you’re going to each different person you can have so many different appointments.”

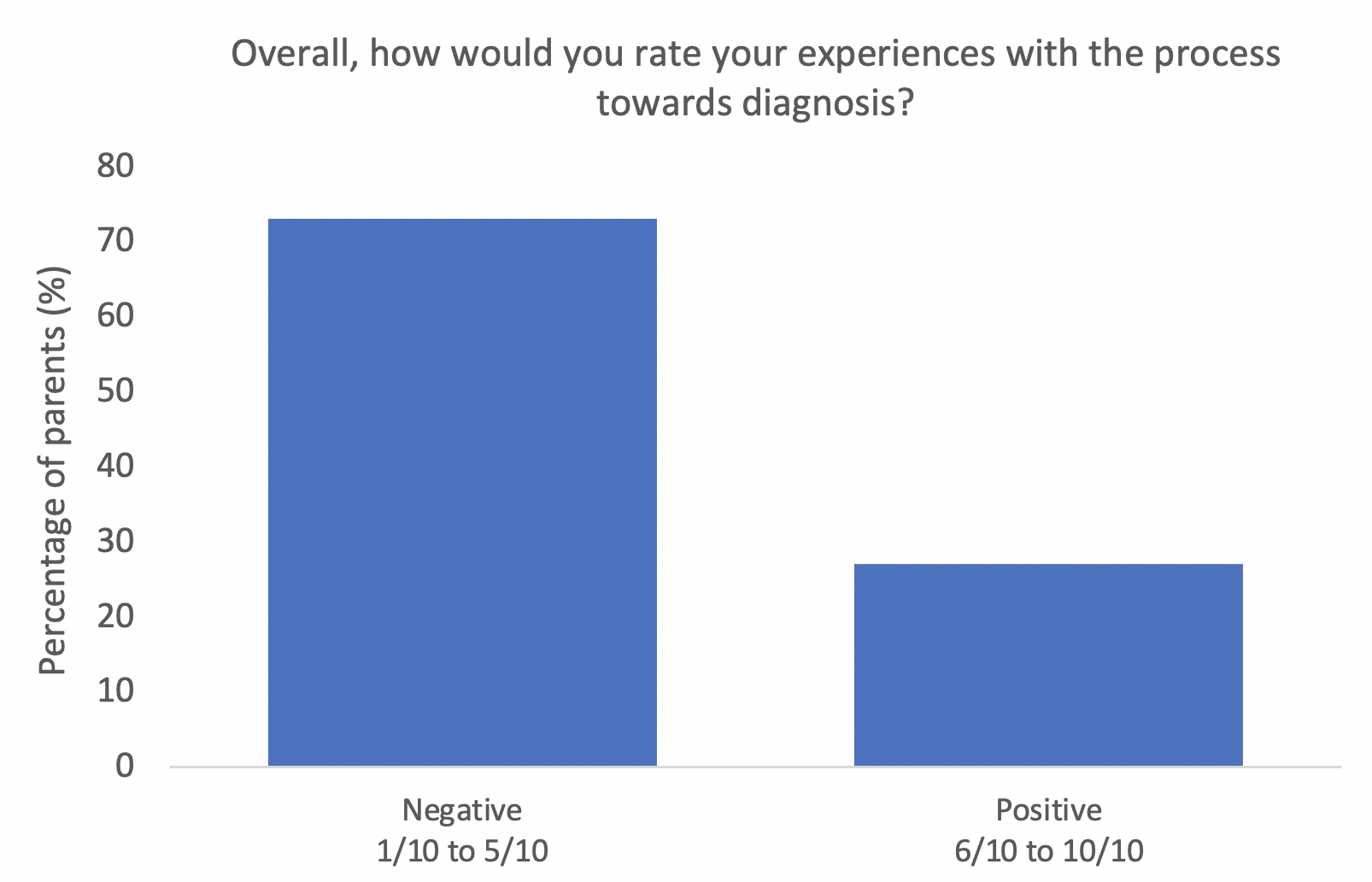

When asked to rate their overall experience with diagnosis out of 10, three quarters of parents rated their experience negatively, scoring the process 5/10 or less.

One third of children diagnosed with hEDS/HSD were diagnosed within 6 months to 2 years of first accessing health care, though children suspected to have hEDS/HSD had been accessing health care for over 4 years so far. Interviewed parents also reported that they attended private healthcare to speed up the diagnostic process. Often, a diagnosis of hEDS/HSD could be reassuring for families and provided an answer for symptoms. However, access to treatments and specialists could also remain challenging after diagnosis. Some parents had also received incorrect comments that a diagnosis of HSD was less severe than hEDS. This is not the case, and both hEDS and HSD can include the same severities of symptoms.

“I don’t feel very confident that we’re going to get a straightforward route to diagnosis.”

What do the findings mean for children’s health care?

The findings contributed some important recommendations for children’s health care, as well as highlighted how research and practice could be developed moving forwards.

- Health professionals should collaborate with families, be proactive in learning about hEDS/HSD, and listen to families’ lived experiences.

- A more coordinated and joined up health care system would help different specialties to work together to support families.

- Diagnosis can support people to understand their symptoms and health conditions, and so can be beneficial even when potential treatments remain unchanged. Increased education and awareness could reduce wrong assumptions associated with certain diagnoses (e.g. HSD).

- More research is needed with health professionals to understand their knowledge about hEDS/HSD and how it can be improved. Speaking directly with children with hEDS/HSD is also needed to learn about what is important to them.

- Future changes to guidelines, diagnostic pathways, or other aspects of care should involve children and families, as well as health professionals, to make sure that changes are likely to benefit families.

‘‘That physio was brilliant, she listened not only to me but to [my child] as well. And so, the three of us like a team came up with things that could work, and we figured it out.’’

My reflections

It was a privilege to hear from and speak to parents in this study, and I want to thank everyone who took part, shared, or provided feedback on the project. Alongside learning about hEDS/HSD and health care, I better understood the crucial importance of support networks and in supporting people to have their voices heard. Though this project began as part of my studies, I plan to continue advocating for health care and wider issues for the hEDS/HSD community.

If you are currently a student and thinking about your research project, here are some tips I found useful:

- Start developing and refining your research ideas early on. Make sure to ask about the expertise of your supervisor to shape a meaningful project.

- Engage with the community and speak with charities and advocates from an early stage. This will help shape your research question and design so that it is relevant and important and may increase recruitment to the project.

- Social media is an important way to develop networks and keep updated with developments or research in the area.

- Think about how you can share the results and impact. Working with charities, who may produce newsletters or social media promotions, can be useful to share your findings.

A final thanks to everyone involved in this project! It is great to see what we can achieve when we put our #hEDSTogether

The published journal article can be read here. The paper can also be read on the hEDS Together website here.

Lauren Bell